http://sam-app.org.uk/

Category Archives: e-patient

Guided Medicine or Big Brother: A Thought Experiment

Self-tracking devices have been lauded as the potential solution to filling in the gaps in traditional clinical data collection. Oftentimes, measurements in the doctor’s office are not truly indicative of the patient’s everyday behavior and lifestyle; patients may experience white coat syndrome, or increased anxiety in the presence of the doctor. Automatic self-tracking in everyday living may provide more accurate data because the data is collected in more natural settings.

One of the goals of self-tracking is to model and predict human behavior. This sounds quite promising; however, how does this automated self-tracking actually come about? Would we want our personal handheld devices to predict our next moves? And what a fascinating thought experiment it would be to have our phones, these inanimate devices, give us life suggestions. But oh wait, they do.

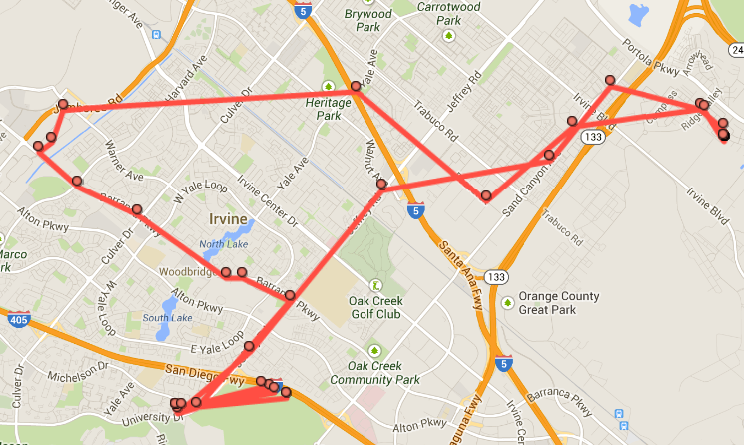

Google Now carefully watches its users’ every interaction to improve its efficacy. It can predict where you will go judging by your past behavior. It can detect that on Wednesdays, you like to get a Grande green tea frappe at Starbucks before your Russian literature class, and sometimes, when you’re having a particularly packed week, you treat yourself and venture into the bold Venti end of the spectrum. While Google Now has the potential to notify you if there is a promotion on green tea frappes, it may suggest another drink perhaps, and as a subtle suggestion, a drink with fewer calories and a lower fat content.

Photo Credit: clipandfollow.com

Popular Science awarded Google Now as the 2012 “Innovation of the Year” for its potential to serve as an “intelligent personal assistant.” It can infer your age bracket from your recent searches and tailor advertisements to your curated predilections. For your mother, it can suggest her favorite hair dyes or jewelry boutiques, but what if one day following her sixtieth birthday, it begins suggesting cholesterol medicine and life insurance? While this teeters on the edge of being mildly insensitive, it may regrettably be a sensible recommendation.

But it doesn’t stop there. Google Now has a minute-by-minute map of your life. Not only can it suggest nearby attractions and events, but it can also summarize your daily physical activity. Given your latest late-night food adventures, it could now suggest restaurants with healthier vegetarian options. It could also suggest a route that requires more physical exertion (to make up for that discreet donut run that you thought went undetected), and in your hurry, you wouldn’t notice that it was slightly more strenuous, with a steeper incline of about two degrees.

Photo Credit: geofffox.com

Physicians have the potential to produce mobile health applications that use the same tracking devices as Google Now. While they have the promise of displaying customized content and advertisements, they can also subtly suggest healthier eats and longer walking routes. With smartphones constantly linking accounts and contacts, mobile health applications will soon be connected to the information collected by Google Now. And suddenly, without your conscious awareness, you will be forced to be utterly and irrevocably healthy.

Instant Access to Yourself

With our constant obsession with technological advancements and the fashionable desire to be the first owner of the newest products, we must remember what we already have. And this isn’t just a banal platitude about being grateful for what we have. Even though the answers to the world’s problems seem to lie in the continued miniaturization of sensors and further embedded systems, have we forgotten what is already available to us? Perhaps we should shift the focus from finding the most sophisticated devices to becoming more proficient with what already exists.

In the summer of 2013, I took a psychiatry course at the Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA. The course had the rather grandiose title: “Personal Brain Management,” yet that was exactly what the physician taught. It turns out that by having a greater control of what we think and how we think can protect us from a wealth of illnesses. The only technological advancement I needed to supplement my project was a thermometer, yet that was enough.

Photo Credit: stress-relief-tools.com

My independent project focused on utilizing biofeedback for Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR). MBSR advocates that practicing mindfulness meditation can help reduce stress and promote greater mental and physical health. By using a simple stress thermometer, I was able to increase my awareness of my body temperature. While such a physiological marker may seem to be beyond our control, managing our internal thermostat is surprisingly possible. Roughly speaking, more relaxed states are correlated with increased body temperature, and the thermometer served as a means to quantify these changes.

With just a crude thermometer in hand, I was able to cultivate my relaxation response (in contrast to the familiar stress response). At the end of a six-week trial, I found that I was better able to control my body temperature, and I scored significantly lower on a battery of stress measures. For my project, I did not need a smartphone or the newest Nike product or the most sensitive sensors. I needed myself and 30 minutes of my day. And am I really so important that I cannot sacrifice the entirety of 30 minutes to myself?

Photo Credit: clintonpower.com.au

In our constant and desperate search for what is new, let’s not forget that we have instant access to ourselves. While innovative electronic devices can help us organize data and take measurements, let’s not get carried away with their seemingly whimsical promises. It is as much our duty to discover and invent as it is to make more effective use of what already exists. By remembering that the first generation of iPhones was released in 2007, we become aware of the humbling reality that perhaps society can function without a supercomputer in hand.

While simple and sophisticated mobile health applications can encourage patients to become more empowered, decreased reliance on digital technology is in its own right just as empowering. My project at UCLA showed me that I could become more self-sufficient and cultivate my body’s natural capacity to heal with a minimalist approach to technology use.

Quantified Self vs quantified self

I’ve mentioned a couple of his videos before, but last week, my favorite YouTube channel—PBS Idea Channel (and the host, Mike)—released an episode titled “How Much Can Data Improve Your Health?”

In the video, Mike talks about the Quantified Self: “that data about or from your body, usually gathered by gadgets, will lay bare and inspire you to improve your body-temple-wonderland.” He mentions that as time passes, gadgets not only get smaller, but also closer to—and possibly inside—the body. With the data we get, we can crunch the data and learn interesting things about ourselves. According to Mike, this is what Whitney Erin Boesel uses to differentiate the ideas of “quantified self” in lower case—having and knowing the data–and “Quantified Self” with title case—knowing and using the data. “Practitioners of the latter don’t just self track. They interrogate the experiences, methods, and meaning of their self tracking practices…”

One interesting thing to think about: what IS the population doing with their data? First, I can talk about this from a personal standpoint. I have two main devices that put me within the Quantified Self spectrum: I have a Nike+ fuel band that tracks motion and a sleep cycle app on my phone that tracks my sleep (side note, I’m experimenting a bit with different apps in the latter to see what kind of information I can get). If we wanted to put me on a continuum for quantified self, I would be unequivocally within the movement (knowledge the movement itself assumed to be a non-issue), but nearer to the “quantified self” end than to the “Quantified Self” pole.

That’s because, while I have this information, I’m not actually using it to do anything. I’m actually content with just the knowledge. Maybe I’d realize that I need to walk a little more tomorrow, or sleep earlier, but I’m still not doing much with all this data I have. Now, I realize that my team’s project has moved away from self tracking per se, but I still feel that this is interesting to talk about for patients and for what we know about patients tracking their data. Being part of the Quantified Self movement takes a LOT of energy (and the motivation accompanying it). I—and Mike as well—have a sense that people who track healthcare information tend to be part of the quantified self movement because of the effort required to be in the other camp. This isn’t a new idea; I’ve talked about it before. Having people put in effort is hard, it is a barrier to access and for patients, and it is a steep hill on the way to becoming more engaged in healthcare. It should be interesting to do a bit more research and learn if self-tracking itself leads to better outcomes, or if the engagement of the self-tracking has that effect.

Another related issue Mike mentioned was about data, “The objectivity of the information upon which they crunch is only just a shade of such….the transition from data to information is not a net 0 process.” He goes on to mention that the data doesn’t necessarily represent reality: “…the existence of a datum has been independent of consideration of any corresponding ontological truth.” This is more of an issue for our group, but it is one we have already considered and are working on a solution. Essentially, patients can give information, but we have no way of verifying its veracity until they are seen by an actual person (and even then, subjective, qualitative experiences like pain still elude external scrutiny), nor can we be sure that correct data represents that which we want to represent. For example, if a patient used our app that we proposed and with it mentioned that they are feeling pain and there is some discoloration of the knee, the patient’s relevant healthcare professionals—a doctor and/or nurses—would be told that there is some potentially severe problem like an infection. Yet the data could show the same symbols if the patient, say, got a tan and bumped it a few minutes prior.

He concludes by noting that the mass produced consumer products that we buy to track health data are often not to emphasize effectiveness in using the consumer’s own data, but rather to compare and compete with other people or with some “fitness ideal” that holds a standard towards which one should be working, because body competition is the focus of a lot of things in our world. Yet, they both allow us to learn more about ourselves, and thus act more effectively in the world.

Mindful mHealth

In the past several years, there has been increased discussion about bringing medicine into the technological era, and out of the darkness of paper methods and inefficiency. Words and phrases like “media,” “digital,” and “mobile technologies”are becoming more and more linked to healthcare. Because we do live in the age of technology, a time when nearly every person in America owns a cell phone (91%) and uses the internet, such a movement seems not only favorable, but necessary. As we push medicine into the digital age, we applaud new, innovative uses of advanced technology for testing, treating, and tracking—for features that allow the new age of “ePatients” to take control of their health.

One of the most “fashionable” new technologies is the mobile app. Apps allow patients to use their mobile phones to track their diet, exercise, blood pressure, etc. With so many emerging uses, smartphones provide a promising avenue to increased ePatient activity. As a result, when people think of patient-centered health media, the first thing that comes to mind is generally mobile apps—or is it?

When I say “people,” this is a very biased demographic. I am a Rice University student in a Medical Media Arts class. While my peers come from very diverse backgrounds, our current lifestyle places us in a specific demographic—that of educated young people who are exposed to mobile technology, specifically smartphones, on a daily basis. Those developing mobile health technologies generally come from similar backgrounds, in that they are most likely very familiar with smartphone usage, and quite possibly own smartphones themselves. For a significant portion of the population, this is not the case.

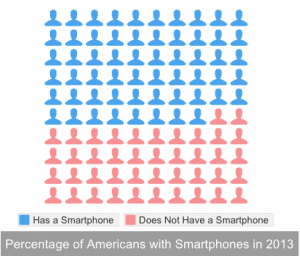

According to Pew Research, only 58% of Americans own a smartphone. While this is more than half of the population, this still means that roughly 131.8 million Americans (42%) do not own a smartphone or have access to mobile applications.

One of the many advantages of mobile technology is its ubiquitous nature and its potential to bridge health disparities by reaching large, diverse populations. However, if all of our focus is placed in a sector of mHealth that such a significant portion of people do not have access to, we are only compounding health disparities with a technological one.

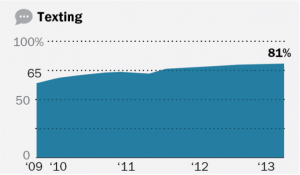

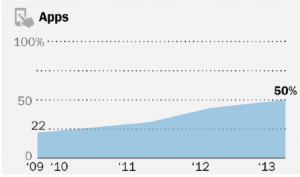

While I believe that mobile applications are a very promising avenue of healthcare, I think that other mobile phone capabilities should continue to be utilized. For example, while only 50% of cell phone owners download mobile apps, 81% send and receive text messages. Text messaging is a simple, low-cost technology, which can be utilized with or without a smartphone, and has consistently been in greater use than mobile apps.

While text message-use is beginning to level-out, mobile app usage is still increasing. However, until the transferral to mobile apps is complete, the “non-app” population should not be ignored. Text message-based mHealth campaigns have already been developed, such as Txt4health, SmokefreeTXT, and text4baby. All of these services promote positive health behaviors by sending text message reminders to patients in the program. We should use these programs as models while we consider avenues that promote patient-centered healthcare and patient engagement, and be mindful of who we are trying to reach and how to best reach them. While mobile applications are a promising platform, which should definitely be utilized, we also have to ensure that we make mobile technologies the solution and not the problem in addressing health disparities.